Warning: This article discusses gear. If you are triggered by talk of photographic gear or suffer from gear acquisition syndrome (GAS), you may want to skip over this column or jump to the end and listen to the video there which supersedes everything I am about to say.

For me, the digital era of photography began with the Nikon Coolpix 995 in 2001. I had largely given up on photography in the nineties. I had grown dissatisfied with machine prints from commercial labs and could no longer operate a wet darkroom at home. Living in the country meant limited water resources and a sensitive septic tank at the other end.

I had already sold my remaining analog gear in favour of a bicycle for exercise and a picture window by my desk to bring the outdoors in when sat there. But a new age of photography was upon us and I yearned to be a part of it. I was already into computers but it would be a couple of years before I traded in my PC for a Mac.

While I had borrowed a Canon S10 as early as 1999 from the small community newspaper I worked at, it wasn’t until 2001 that I laid down some hard earned pay for my first digital camera. At that point, the 995 was already in its 4th generation in the Coolpix 9x series which had begun in 1998 with the 1.2 megapixel Coolpix 900.

The 9x series cameras featured an unusual swivel design that placed the computer and power supply on one side and the optics, viewfinder and flash on the other. The two halfs swivelled against each other to allow the lens to be pointed up or down while the rear display pointed towards my eye. This enabled holding the camera above one’s head to shoot over a crowd or get low to the ground and shoot up at say, the underside of a mushroom, all the while looking at the rear liquid crystal display (LCD) rather than squinting through the underwhelming optical viewfinder, which only showed about 82% of the image and was hard to use with eyeglasses, always a consideration for the bespectacled photographer.

The mostly plastic Nikon 995 sported a 3.14 megapixel 1/1.8” sensor with a maximum output of 2048x1536 pixels and a 4x zoom lens that operated internally, maintaining a fixed threaded front element that could close focus down to 2 cm (0.08 in) in front of the lens. Just to give a sense of how small that sensor was, the usable sensor area was a circle of just over one inch in diameter. The 8-32mm lens had a 35mm equivalency of about 38-152 mm using a crop factor of 4.75. This is close to what camera phones have in them these days, albeit with much more computing power than could have been dreamt of back then.

In hindsight, the ability to move in close to subjects with relative ease was what made this camera so enjoyable to use. The camera’s small sensor and close focusing ability were its superpowers. Two accessory lenses (a wide angle and a telephoto) could be threaded onto the front of the lens although I never purchased either of them. At over $1500 for the camera alone it was already quite expensive. A massive amount compared to what the same money will buy you today.

While it didn’t have manual focus, it was easy enough to prefocus by depressing the shutter halfway down, then moving the camera back and forth to get the composition right before pressing further to take the picture. I rarely used the optical viewfinder on this camera as it was quite useless, and it soon became second nature for me to shoot holding the camera out in front of me. The camera was also the first of the Coolpix series to use a rechargeable battery instead of 2 AAs. For it’s time, it was one of the most popular prosumer cameras on the market, but of course it quickly became obsolete. Despite that, I kept using it for most of the decade.

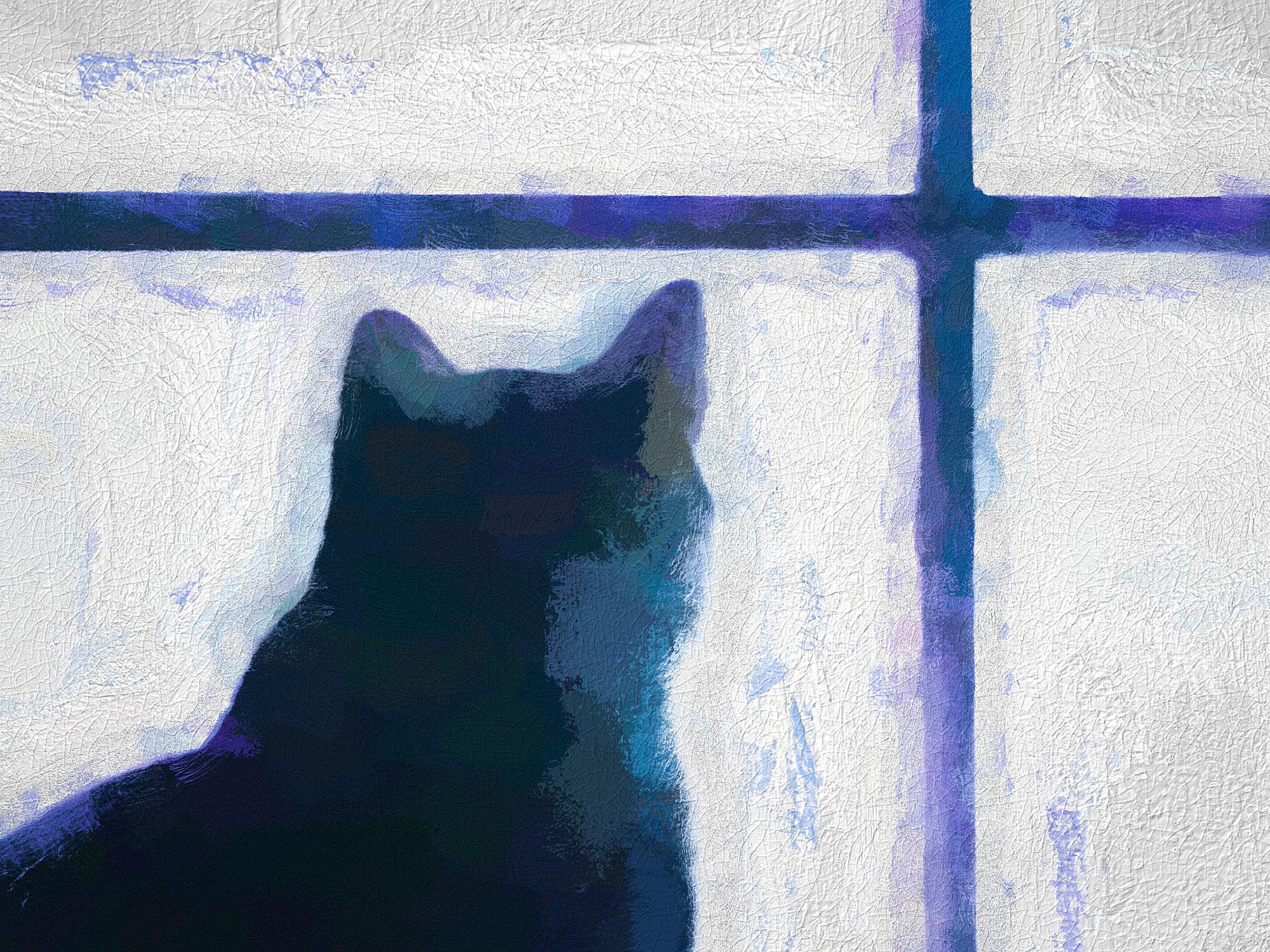

The relatively small images (2048 pixels wide) the camera produced encouraged me to find ways to improve output quality through upsampling and post processing programs such as Photoshop and Topaz Studio which pixel pushed images towards a more painterly end result. I was always impressed by the ease of use and large number of infinite variables Topaz permitted which combined with my subject selection, allowed me to develop my own style.

Despite the head scratching this caused both photographers and painters, I quite liked some of these efforts and remain interested in paint applications to this day. Further development of the Topaz Studio suite improved masking techniques to make combinations of filtration to various parts of any given image quite helpful. My first post here on substack is another example of using post processing to enlarge small files enabling larger, more painterly prints.

It was during this initial period of my digital journey I decided I didn’t need to go to exotic or popular tourist destinations to get dramatic or outstanding pictures. In fact I didn’t need to go anywhere. I just needed to open my eyes and see the beauty that already surrounds me.

I was encouraged by the book Photo Impressionism and the Subjective Image by Freeman Patterson and Andre Gallant, to re-examine the world I had immediate access to and how I might interpret it. It seems familiarity breeds blind spots when it comes to recognizing the incredible beauty and sensuousness that lies at our doorstep. But what is common place to us can be exotic to a person from away, so our perception is really the only thing that keeps us from seeing what truly lies in front of us. Once I understood this, it became my goal to open my eyes, awaken my senses and capture the beauty in the everyday. I understood that beauty is often fleeting, but if we are attentive, if we are curious and creative and we show up, then we will be able to capture moments of local bliss and if we are skilled enough, hold onto beauty’s fleeting nature. This to me, is the power of photography.

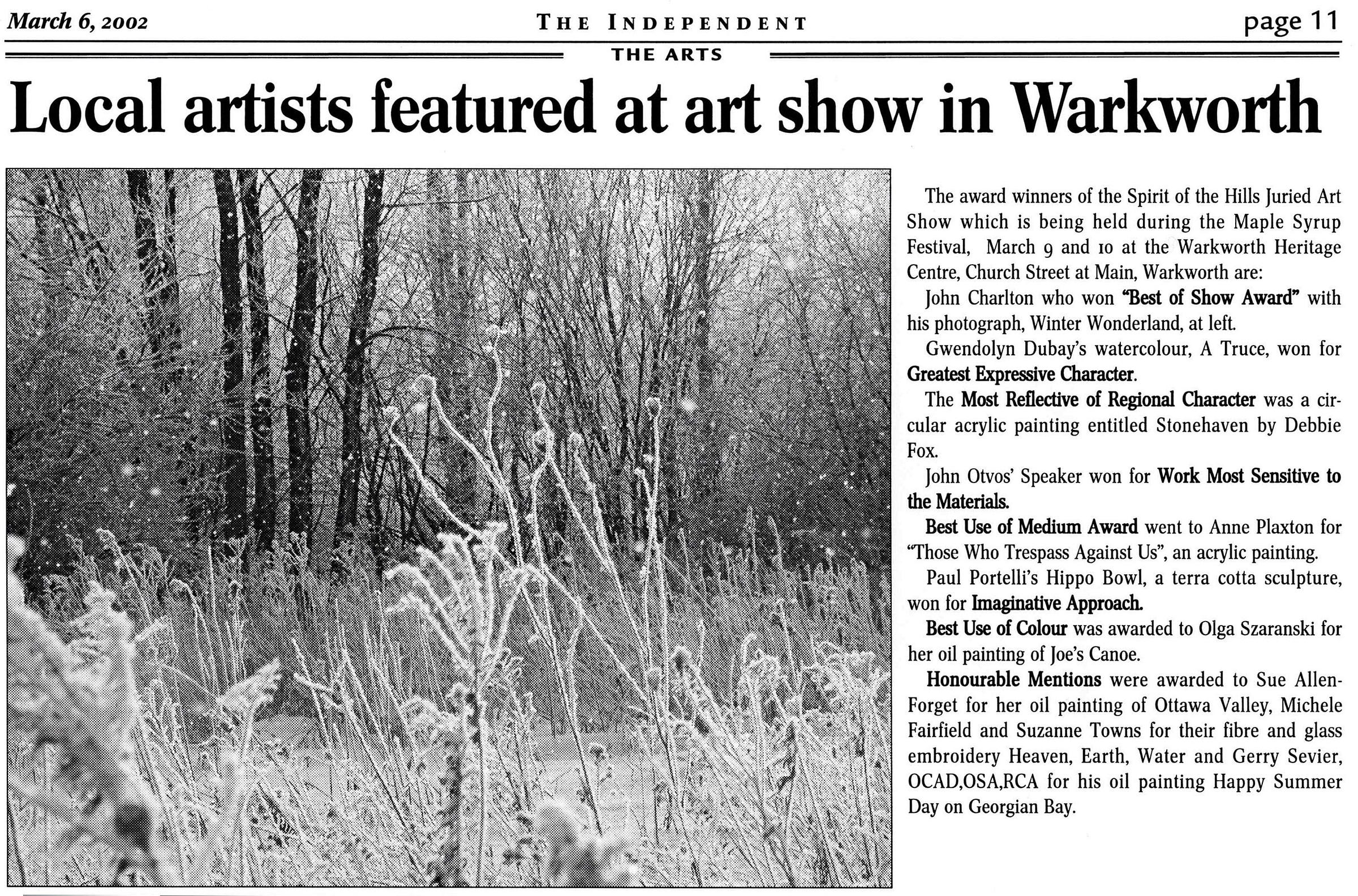

The photo above, Winter Wonderland won Best of Show at the 2002 Warkworth Maple Syrup Festival art show against a strong field of creatives including painters, sculptors, fiber artists, cabinet makers and fellow photographers. While a few people were shocked by this turn of event, I found it gratifying to be acknowledged for recognizing beauty in the familiar.

In my next camera talk article, I’ll continue my digital journey speaking about my subsequent years with Panasonic Micro Four Thirds cameras.

Creativity is a Gift

In the meantime, I leave you with some wise words from Freeman Patterson about creativity and our roles as creators. As he points out, the tools we use are not important. Creativity is what we as sentient human beings bring to our work.

Creativity is the fundamental gift of life and using it is our fundamental responsibility.

Freeman Patterson

This sounds about the same as my initial steps into digital. We weren't really a photographs kind of family; we had a Vivitar 110 which I took ownership of when we "upgraded" to a Kodak 110 but I didn't really get interested until the late 1990s. Bought a Canon Sure-Shot and annoyed everyone by taking lots of photos at work events and such. Not a great camera really, so when I encountered a digital camera for the first time, I was intrigued. My first (some Casio, a QV4000 maybe, I bought in 1999) was pretty meh, even the Canon outperformed it. But the instant feedback was gratifying.

Quickly replaced it with an Olympus C4000Z which was my only camera for almost a decade. I think that little camera is the reason I became actively interested in photography as something more than just a way to document everyday things. It had just enough capability to be interesting and provide a means to experiment with the medium, and was good enough to make quite pleasing 8x10 prints from.

Very cool what you did with Topax!