In 2010, my wife and I visited Beamish Open Air Museum near Stanley, County Durham. It’s a remarkable place where history comes to life. I was particularly interested in seeing the mining operation there, as it gave me a unique glimpse into the lives of my coal mining ancestors.

Stepping through the entrance, we could see the pit head off in the near distance, pictured above with its winding mechanism perched atop a large shaft designed to haul men in and out of the mine along with their hard earned bounty. In the distance a replica of a Victorian era town.

The day was overcast and threatening rain. Typical North East weather. It looked like this would work in our favour as the parking lot outside the facility was almost entirely empty. We arrived early and were able to park near the main entrance. It seemed for the moment at least we were to have the museum to ourselves. I didn’t mind the rain. It just seemed to lend authenticity to the day. We walked down from the entrance to the colliery gates.

Reviewing my images, there are some which stand out and continue to hold meaning for me after all these years. Those are the ones I would like to share with you today.

I have enhanced the images in post processing, converting them to moody remembererences of an unforgettable day.

Beamish strives for authenticity, but acknowledges it is a museum and not a working mine. There are abandoned rail tracks leading to the pit head. The resulting sense of nostalgia is amazing to behold.

Above is a closeup of the main piston of a steam locomotive parked at Beamish. According to this article, it was built by the South Durham Steel and Iron Company. The locomotive has since been given a complete makeover in 2018, although I kind of liked it with the rust. It has now become part of the Beamish Museum permanent collection.

The industrial revolution was completely dependent on steam engines. Everything that went to market was moved by rail, on wheels like this one.

This is an industrial landscape. Everywhere you turn you see things made of steel. The steps leading to the pit head, the railings, all held together with industrial sized nuts and bolts. We climbed these steps into the pithead building and up to the sorting station.

Inside the pit head, the conveyor belt stands still, the workers, most likely children, long gone. It’s as if a whistle had blown and everyone had just left the building.

But not all were gone. A banksman (actually a Beamish Museum tour guide) watches as I photograph a cart full of timbers waiting to be loaded onto a deck and lowered into the mine.

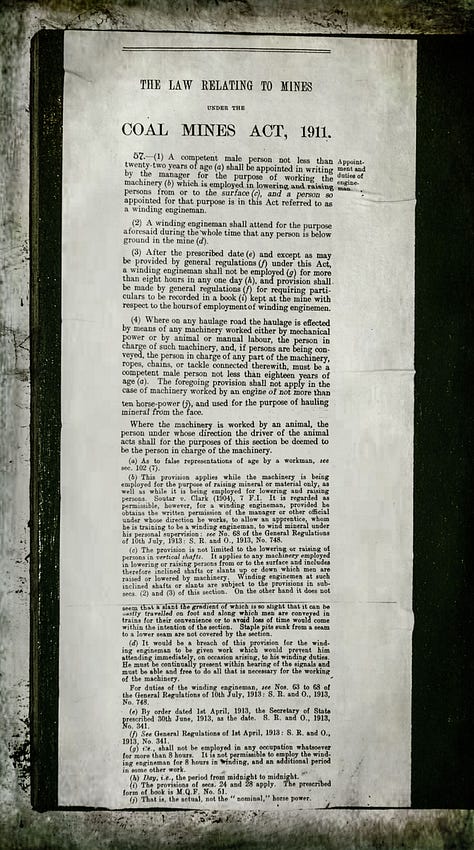

While the majority of men were miners working the coalface deep underground, some were given jobs of great responsibility within the pit head and at the shaft face underground. Everything that came and went to and from the mine was done so with the assistance of a dedicated group of workers.

This was largely the domain of many of my ancestors, including my great grandfather W. B. Charlton who was Secretary of the Union that represented them, himself having been a Banksman and Winding Engineman for many years and subsequently a union representative before being elected to high office. In addition to being a Union leader, he was a Justice of the Peace in Durham City Court and a lay preacher at Old Evet Methodist Church. Additionally, he was one of the pioneers of the Aged Miners Homes which provided housing for miners who made it to their retirement years. Of course, not all did.

The non-miner rolls these men played were specific and vitally important to the smooth and safe operation of the mine. Winding Enginemen, Banksmen from above and Onsetters from below, coordinated the activities.

A sign on the left explains the signals to be strictly followed. The numbers represent the clang of a hammer on a metal component of the shaft. The rapped sound carried quickly and efficiently long before radio communications allowed for more direct conversation. The banksman at the top of the shaft and the onsetter below used these signals to communicate with each other and coordinate the loading and movement of the cages within the shaft.

First, some quick definitions of the roles of various workers above and below ground related to the raising and lowering of miners, ponies, coal and other materials within the shaft.

Banksman: The person loading and unloading the cages at the top of the shaft.

Onsetter: The person loading and unloading the cages within the mine.

Winding Engineman: The person operating the cable mechanism with the aid of a steam engine. This was done from an adjoining building connected to the shaft by some massive wheels and miles of cable.

Firemen: The people who kept the steam engine running by shoveling coal into a furnace which allowed the cages to be raised and lowered by the Winding Engineman.

BEAMISH 2nd PIT SIGNALS

The following signals shall be used at all times in connection with winding in shafts.

FOR WINDING PERSONS (Prefix numbers below represent the number of raps to be made for each of the following signals)

3 - When a person is about to descend the Banksman shall signal to the Onsetter and Winding Engineman

3 - Before the person enters the Cage the Onsetter shall signal to the Banksman and Winding Engineman

2 - When the person is in the Cage and ready to descend the Banksman shall signal to the Windingman

1 - And the Onsetter shall signal to the Banksman and to the Winding Engineman

3 - When a person is about to ascend the Onsetter shall signal to the Banksman and Winding Engineman

3 - Before the person enters the Cage the Banksman shall signal to the Onsetter

1 - When the person is in the cage and ready to ascend the Onsetter shall signal to the Banksman and the Winding Engineman

2 - The Banksman shall signal to the Winding Engineman

6 - Persons going to Shield Row Seam

7 - Persons going to Five Quarter Seam

8 - Persons going to High Main Seam

9 - Persons going to Low Main Seam

The Raps 3 and 2 from Bank or any Seam will mean to the bottom.

Not more than 4 persons to ascend or descend in each deck.

FOR WINDING OTHER THAN WITH PERSONS

1 - To Raise Up

1 - To Stop When in Motion

2 - To Lower Down

4 - To Raise Steady

5 - To Lowerer Steady

10 - Clear Cage

Hang (obscured) Coal (obscured)

On the right of the picture, another sign reads:

NOTICE.

No person other than the Banksman or Onsetter shall give any signal, unless he is an official of the mine, or is authorised by the Manager to give signals.

Stepping outside from within the pit head, we found ourselves looking out at a single cart on an elevated section of track that led to a slag heap. These were the flotsum and jetsum discarded at the sorting station. Was this the sort of place my great grandfather would have worked when he started at Edmondsley Colliery at 8 years of age? The quietness of the museum seemed to clash with the images that flashed in my mind of the bustle of activity that it once was. Nearby, a Jackdaw, or was it the soul of a miner, stands guard, sizes me up, and moves on, apparently unimpressed by my presence.

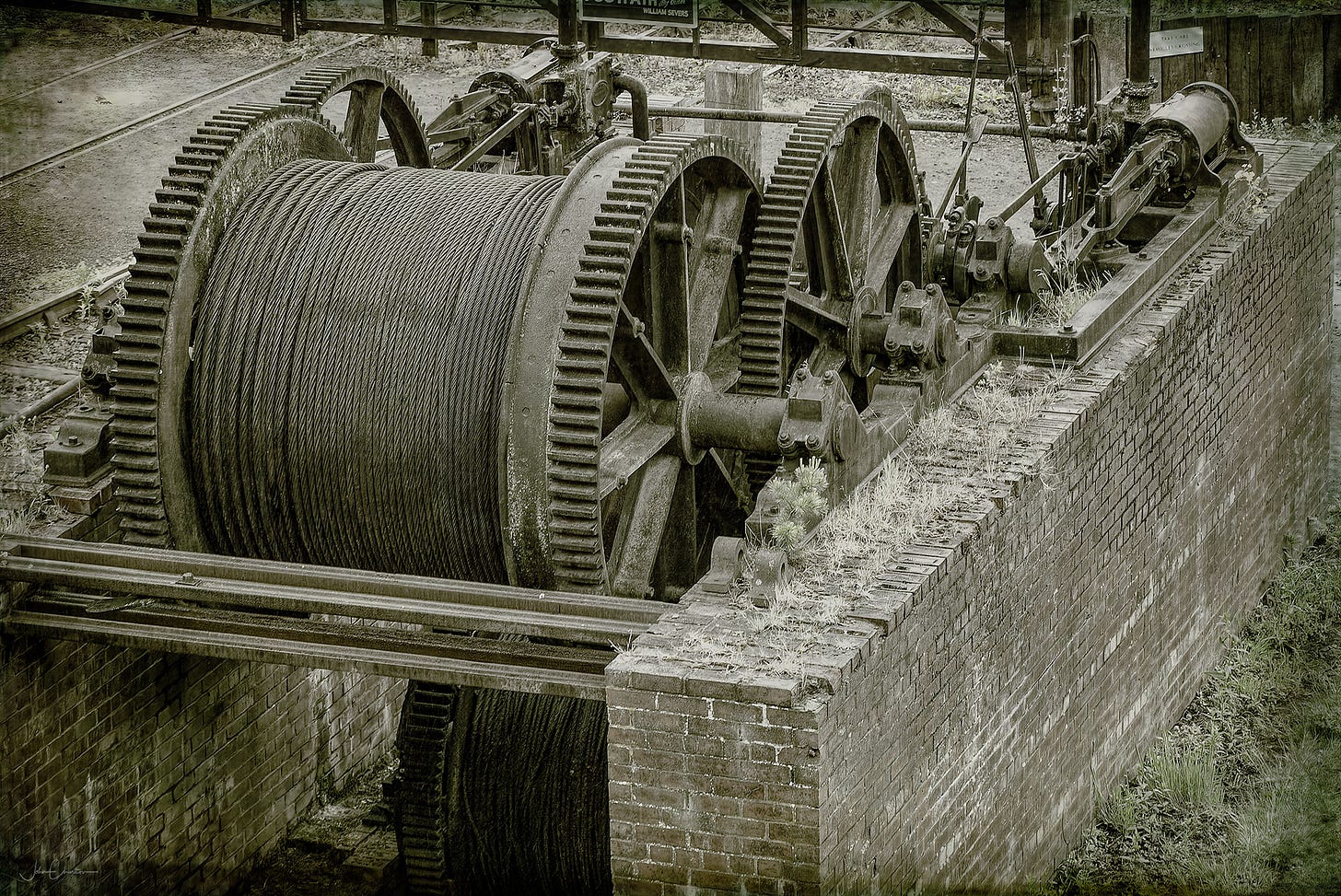

The view from the elevated track allowed us to look around at the yard. In one direction, tracks led to another engine shop, while just below us sat the winding rope.

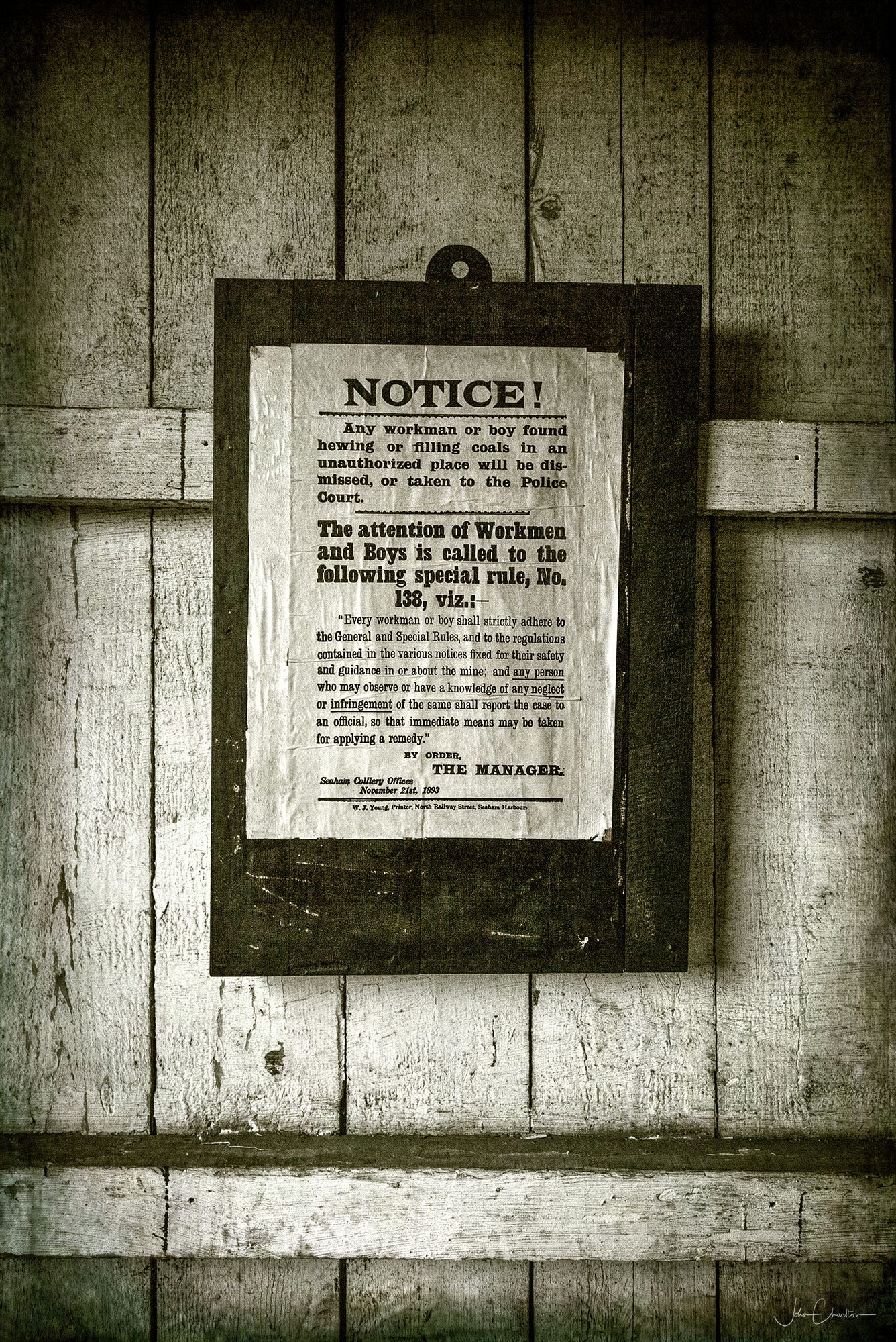

Mining was serious work and although there were many children on site, there was no time or tolerance for fooling around as indicated by Special Rule No. 138 below.

Leaving the shaft from halfway up, we headed down an elevated ramp toward the winding engine house which sat next to it. Above our heads, the winding cable that lifted the cages up and down using the large pulley at the top of the shaft. The one we could see we could see from the entrance of the museum grounds.

Steps leading into the winding engine house from the second floor entrance shone brightly in the rain.

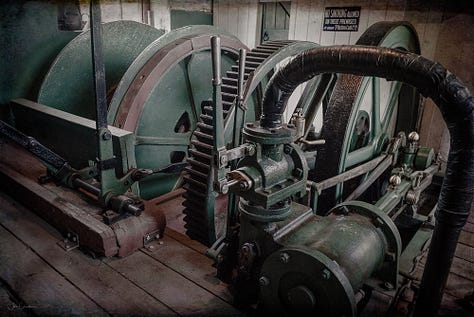

The heart of the operation is the winding engine room. This is where the winding engineman controls the cages, lifting them in and out of the shaft as needed. This is done using large hand levers. It is easy to see why this role was so critical. Enginemen held the lives of the miners in their hands and their dexterity and attention to detail could mean the difference between a normal experience and disaster. Because of the winding enginemen in my family, I gave the winding engine room particular attention. I was fascinated by all of the gear found here. All very technical and mysterious. Dominated by large pistons, heavy cable and steel cylinders, I’m sure it took some time to learn the wherewithal of it and to be trusted with its operation.

Another set of stairs and we were back on ground level outside again. Looking up, we could see the elevated track leading to the slag heap where we had seen the cart and the jackdaw.

Behind us, the engine winding house we had just left. A large stone building designed to hold the industrial sized equipment necessary for the operation of the mine.

Power to the winding engine was supplied by a boiler located in a nearby building and connected by a steam pipe. The men who ran the boiler were called firemen and they were basically tasked with keeping the stream coming.

Time to go into the mine. At Beamish there is no need to be lowered deep into the ground to visit the coal face. A tunnel has been cut to the coal seam a short distance into a nearby hill. Passing through the lamp house where miners would pick up their gear, we walked into the mine. Good thing we were wearing hard hats. Otherwise, I would have knocked myself out cold several times before reaching the coalface not far away. Far enough however for it to be dark. Pitch dark.

Maybe it was the blows to my head on the way into the mine, but I saw something down at the coal face I couldn’t quite explain. Perhaps I’ll just leave the mystery be.

We thoroughly enjoyed our visit to Beamish. We took a trolley down tho the Victorian Village and had some meat pies, but the mine tour was for me the connection with the past that I had come for.

Till next time

John

Some parting music to leave you with:

Great to see this John, I can't imagine how long it must have taken you to put together. Beamish is about 45minutes from where I grew up in Northumberland, so I've been there quite a few times. Thanks for taking me back there today!

Great to revisit Beamish through your writing and photographs and I enjoyed reading about your family history too. W. B. Charlton sounds like a really impressive person who made a difference.